War(gaming)! What is it Good For? Absolutely Something.

Formal conflict simulations (wargames) have been used for centuries. I give three reasons why.

In a previous article I briefly introduced Wargaming, and the pursuit of wisdom. Another common term for wargaming is 'conflict simulation.' This article discusses three uses of conflict simulation and why they're all pretty cool.

Conflict simulations (wargames) enable active learning for both players and designers, help us challenge poor assumptions, and can predictably uncover unknown-unknowns. Combined, these benefits make conflict simulation indispensable in the realm of decision-making affairs.

To unfurl this banner, we will 0) briefly review what conflict simulation is, 1) discuss how it leverages active learning, 2) understand how it challenges our assumptions, and 3) consider how conflict simulation helps us uncover unknown-unknowns.

Yahoo!

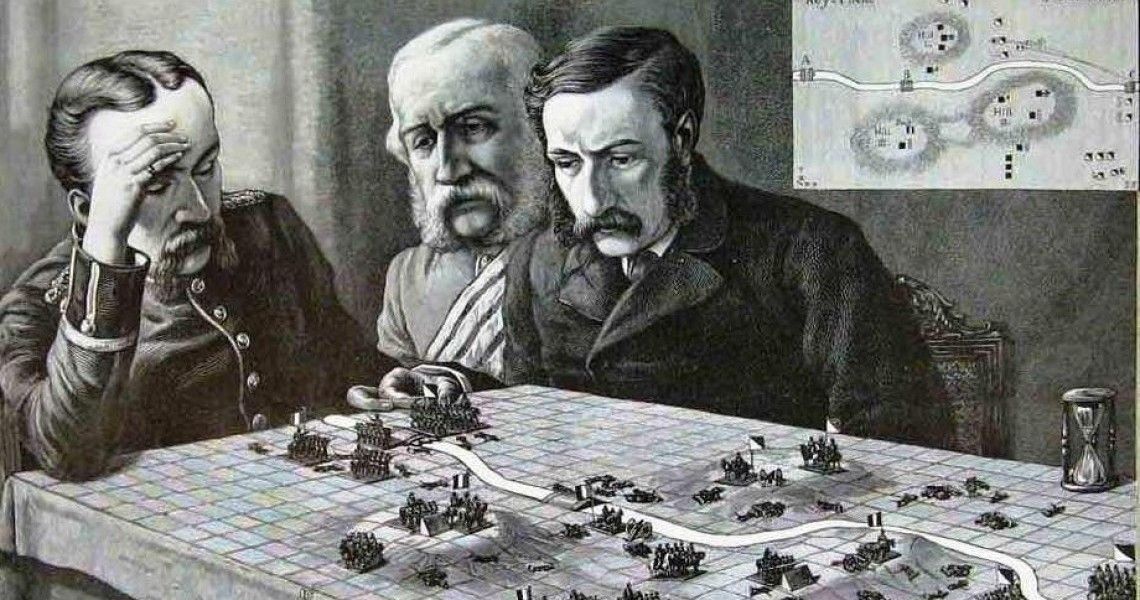

0) Remind Me... What is 'Conflict Simulation'

Conflict simulation is a synonym for wargaming. One of my favorite definitions is given by Dr. Peter Perla:

"In its broadest application, the term wargame is used to describe any type of warfare modeling, including simulation, campaign and systems analysis, and military exercises." (pg. 252, Peter Perla's The Art of Wargaming)

I prefer the term conflict simulation because the fundamental tools and use cases expand beyond armed conflict to all forms of human conflict - including non-violent ones. Philip Sabin expands upon Perla's definition:

"The key characteristic uniting war and games, and which sets them apart from most other human activities, is their competitive and agonistic nature." (pg. 12, Simulating War)

and

"Both war and games pit humans against one another in a dynamic interactive contest of wits and resources, as the opposing sides struggle to prevail." (pg. 12, Simulating War)"

I claim that Oxford-style debates, business competition, interactive case studies, and many other forms of human conflict fit this definition. Principally for this reason I use the term conflict simulation.

"(Jim) Dunnigan, as usual, made the pithily appropriate comment that: ‘A wargame is a playable simulation. A conflict simulation is another name for wargame, one that leaves out the two unsavory terms “war” and “game”.’ " (pg. 29, Simulating War)

Wargaming suffers from a poor reputation in many quarters. There very idea of 'playing at war' in a 'game' is offensive to some; it can sometimes carry the stigma of callousness or worse.

As mentioned earlier, see another article for a more in-depth description of conflict simulation.

1) Active Learning

For the past decades the field of education has been excitedly integrating active learning into its curricula. Active learning is:

"[...] a method of learning in which students are actively or experientially involved in the learning process and where there are different levels of active learning, depending on student involvement." (Wikipedia, citing Bonwell & Eisen (1991))

So many studies have empirically demonstrated that students learn better when they are interacting with material being taught - getting their hands dirty and personally involving themself in the material they're learning. "[P]lay, technology-based learning, activity-based learning, group work, project method, etc." are all examples of active learning modalities.

It is not difficult to see how conflict simulations (wargames) can serve as active learning opportunities for students.

"Wargames are, of course, an advanced form of ‘active learning’, as opposed to the passive absorption of information transmitted by the teacher." (pg. 75, Simulating War)

What are students learning? That, of course, depends greatly upon the simulation in question. I think there are two types of active learning taking place:

- The subject material (theme?) that the simulation attempts to communicate to the player (student).

- Player experiential role assumption and decision-making under constrained and challenging conditions.

Perla goes on to say:

"By involving the player as an active participant in the events, not merely as a passive observer, wargaming provides a unique learning experience that leads to a deeper and more personal understanding and appreciation of [conflict] than can be attained by any other method short of actual participation [...]." (pg. 30, Peter Perla's The Art of Wargaming)

It may make immediate sense that wargames or conflict simulation are active learning for the students (players). What about designers?

"However, just as the best way of learning about a subject is to have to give a presentation on it oneself, so the greatest insight to be gained from conflict simulations comes from designing them rather than merely playing them." (pg. 82, Simulating War)

Sabin gives further advice to conflict simulation designers, as well as teachers intending to use them as an active learning tool:

"[T]he single most important element is that teachers should be bold enough and flexible enough to seek to inspire students using whatever approaches they themselves have found most interesting and inspirational, rather than sticking to conventional educational techniques just because they are easy and uncontroversial." (pg. 89, Simulating War)

2) Examining Your Assumptions

A difficult thing to do in life is to challenge your own assumptions. Conflict simulations can be excellent tools to assist in this endeavor. Here, I'll look at how we can examine our assumptions on models, game theory and rational actors, and the decision-making environment.

Building and Validating Models

Models are the simultaneous bane and salvation of analysts everywhere. Models allow us to understand relationships between related factors, inputs, and outputs, however they are all 'pleasant fictions' that have limits in their accuracy, precision, and application.

For the conflict simulation designer this presents a dilema: 1) how much detail should the model capture and 2) how can the model be validated?

Perla dispenses his perennial wisdom on this matter:

"The debate about the validity and utility of mathematical models of [conflict] is probably as old as the practice of devising them." (pg. 349, Peter Perla's The Art of Wargaming)

In conflict simulation, modeling is often based on historical precedent. Examining historical events, attempting to understand their factors, inputs, and outputs, and mathematically modeling them is the name of that game.

Needless to say such an endeavor is fraught with pitfalls. Even with highly documented events.

"Even knowing in some detail how a historical engagement turned out takes us only part of the way towards having the information necessary to simulate it, since simulation modelling is a far more ambitious process than mere narrative description of the events concerned." (pg. 103, Simulating War)

Regardless, from a philosophical and research perspective, modeling presents several opportunities:

"As a tool of research, then, modeling succeeds intellectually when it results in failure, either directly within the model itself or indirectly through ideas it shows to be inadequate. This failure, in the sense of expectations violated, is, as we will see, fundamental to modeling." (William McCarty, Modeling - A Study in Words and Meanings, A Companion to Digital Humanities)

Another benefit of conflict simulation is understanding how a historical event is related to the probability distribution of possible outcomes. Was the historical event an outlier? Representative?

"The trouble is that the only really reliable data on which to base this model come from a single historical ‘trial’." (pg. 103, Simulating War)

and

"A second, related question is whether the real outcome should lie in the centre of the wargame’s probability distribution, or off to one side." (pg. 104, Simulating War)

Depending on the scale of the subject matter (i.e., tactical or operational events) we may have multiple events (data points) with which to begin answering this question. For matters of grand strategy we are forced to look across larger spans of time. This introduces its own difficulties and confounding variables.

Sabin concludes on this topic, emphasizing the degree of predictive and counterfactual power that conflict simulation supplies:

"[W]argames are rather like weather forecasts–their reliability diminishes quickly the further they look beyond what we already know [...]" (pg. 117, Simulating War)

Now that we have an idea of the sandy foundation of conflict simulation modeling, let's discuss one of the most vexing questions - that of player decision-making.

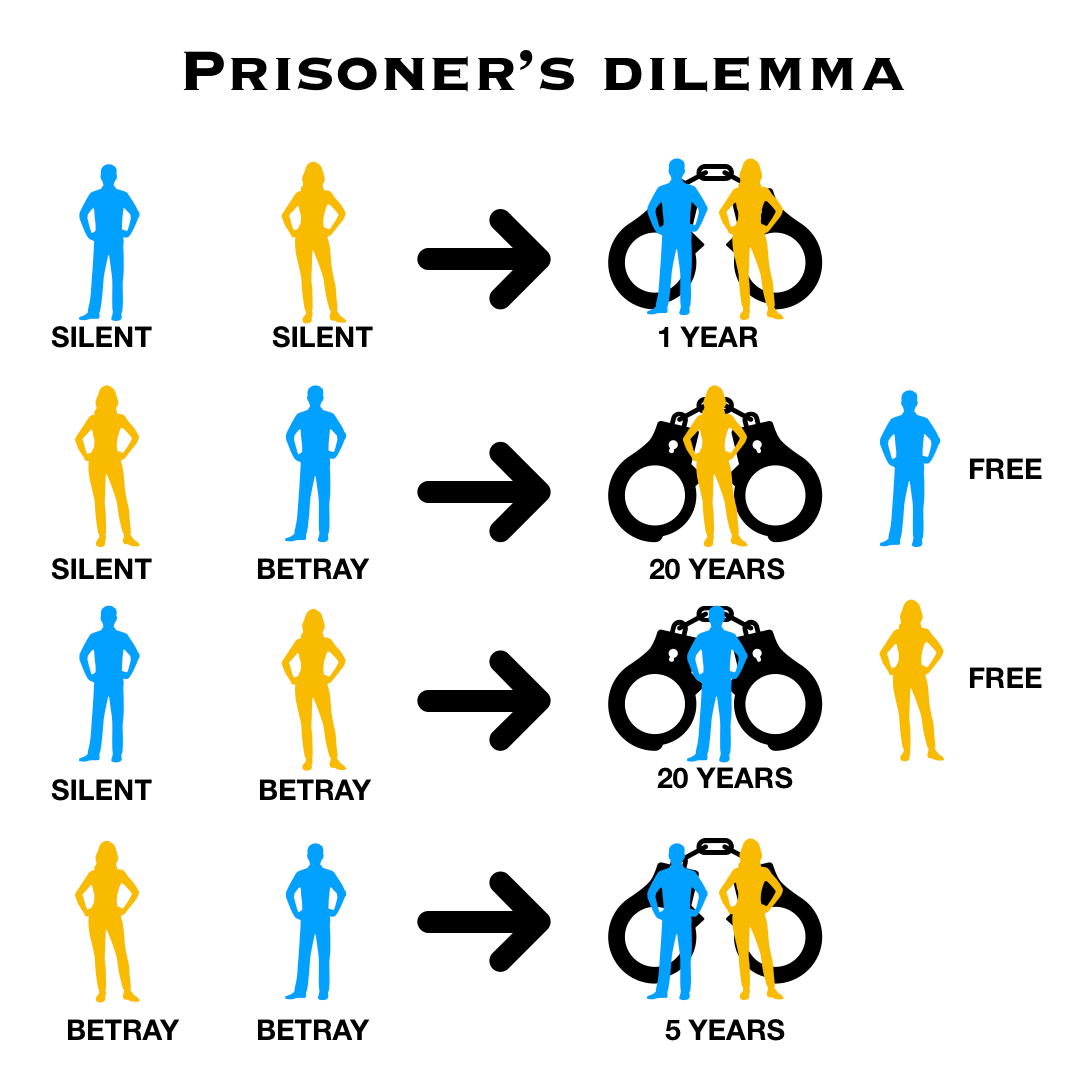

Game Theory and Rational Actors

How rational are actors in their decision-making during conflict? Can game theory be successfully applied to conflict simulation? Having taken game theory courses and applied their principles in academic research papers, this topic is near to my heart.

"However, in his 1960 book on The Strategy of Conflict, economist Thomas Schelling took the military application of game theory in a new and broader direction." (pg. 38, Simulating War)

Dr. Schelling later won a Nobel Prize in Economics.

"By manipulating the relative numerical payoffs associated with the different [decisions], Schelling and similar theorists sought to model three different kinds of superpower competition." (pg. 39, Simulating War)

Ah, grand strategy and nuclear deterrence!

"The final and most nightmarish scenario was one in which the vulnerability of both side’s nuclear arsenals to a first strike created a ‘reciprocal fear of surprise attack’, such that the least bad option was to fire first even though the ‘victory’ this produced would in this case be far inferior in value to that obtainable by avoiding nuclear war altogether." (pg. 39, Simulating War)

The paradoxical conclusion that, under rational decision-maker assumptions, a nuclear first strike is a plausible solution to nuclear deterrence should chill us all to our marrow.

"After the first flush of enthusiasm, doubts soon emerged about the legitimacy of comparing the choices made by stressed, biased, ill-informed and fragmented military or political bureaucracies with the decisions of rational, amoral, unitary ‘players’ concerned only with maximising their payoff in an artificial game." (pg. 40, Simulating War)

I think this is a valid criticism. Game theory and rational decisions depend greatly upon the objective functions and assigned values for different outcomes. What if these are unquantifiable using mathematics? What if they are simply unknown (or unknowable)? Whether it is a rational decision or not, decision-makers in conflicts are not omniscient, nor are they all operating on the same (or even quantifiable) cost functions.

The promise of game theory (completely) solving our woes with an easy victory is dashed from our lips in complex grand strategy applications.

"Even the simple abstract games [...], whose rules could be outlined in a single paragraph, produce interactive decision dilemmas that could keep game theorists busy for a long time analysing the best choices at each stage." (pg. 180, Simulating War)

Further:

"Human players can recognise such circumstances and make such prudent decisions, and the resonant interaction between the decisions of competing players on the two opposing sides creates subtleties and complexities that traditional mathematical modelling finds it hard to capture." (pg. 180, Simulating War)

There may be hope for game theory in grand strategy, but that is an article for another time.

Decision-Making Environment

A defining feature of conflict simulation is its ability to have players assume decision-making roles. Perla expands on this:

"Its forte is the exploration of the role and potential effects of human decisions [...]." (pg. 253, Peter Perla's The Art of Wargaming)

Role-playing involves assuming the role or persona of an individual in a social or organizational structure. Because the decision-making environment is also a potential flaw in theories depending upon rational actors, it is especially important to emulate in conflict simulations.

"Last but by no means least researchers must explore the decision environment facing the real commanders, including such aspects as intelligence, the fog of war, command and control capabilities, and the influence of political considerations and strategic culture." (pg. 92, Simulating War)

Perla agrees:

"Wargames [...] can help the professional commander and staff officer experience decision-making under conditions that are difficult or impossible to reproduce in peacetime." (pg. 38, Peter Perla's The Art of Wargaming)

Indeed; player decision-making is the principle object of interest in using conflict simulations to investigate

"Players in professional wargames must understand that their decision-making processes are the key subjects of the games' investigation or instruction." (pg. 39, Peter Perla's The Art of Wargaming)

Onward towards the unknown...

3) Unknown-Unkowns

I've previously written about how knowledge is manufactured and kept. One recurring theme are unknown-unknowns - knowledge you didn't know that you didn't know. In this context we can view these as questions we have not thought to ask and do not have evidence to resolve.

Conflict simulation excels at uncovering these unknown-unknowns - problems cloaked in ontological uncertainty - and converting them at least to a question we can ask (and hopefully answer).

Certainly, this can happen when we actually play conflict simulations. At the risk of giving entirely too many quotes, I'll lean on Perla's sage observations:

"Wargaming forces participants to look at reality from a different angle and can lead to fundamental changes in how they see that reality." (pg. 274, Peter Perla's The Art of Wargaming)

"As an exploratory tool, wargaming can give players, analysts, and other observers and participants new insights, which can lead them to further investigation of the validity and the sources of their beliefs." (pg. 274, Peter Perla's The Art of Wargaming)

"There is a potent value in unpredictability, and in exposure to the antagonistic will of another who is operating on the basis of very different assumptions. Neither of these values can be derived from solitary meditation or cooperative discussion." (pg. 181, Peter Perla's The Art of Wargaming)

"[I]nvolvement and excitement produce the atmosphere of intense competition that can lead to the development of original ideas so important to the value of the professional gaming." (pg. 357, [[Peter Perla's The Art of Wargaming]])

Certainly, unknown-unknowns can be uncovered through using conflict simulation and engaging in active learning. It should perhaps be no surprise that conflict simulation designers can uncover unknown-unknowns as well. Sabin explains:

"Just as the use of wargames for education and training has hitherto been a predominantly military endeavour, so the use of wargaming as a research device has been far more a matter for military professionals and defence analysts rather than civilian academics." (pg. 108, Simulating War)

"[T]he way in which designers themselves learn through the iterative testing and tweaking process as their system comes to life and generates insights and questions that had not been anticipated beforehand." (pg. 413, Simulating War)

There are precious few tools that can predictably uncover unknown-unknowns. Conflict simulation is one of them.

Summary

We arrive at the end of our tale. Let's summarize.

- Both players and designers of conflict simulation participate in active learning. Players engage in active learning when they grapple with systems, one another, and decision-making, and designers do the same when they attempt to design and form conflict simulations to examine specific questions.

- Conflict simulation helps us challenge our assumptions. Whether it is the models being used, and conceptions of what rational actors would do, or the environment in which these decisions are rendered, conflict simulations test our assumptions. This is a good thing.

- Conflict simulation can predictably uncover unknown-unknowns. Very few tools have the ability to regularly and predictably identify new questions that we need to answer. The ability to mitigate 'failures of imagination' is a hallmark of wargames.

Subscribe to the Newsletter

If you enjoy this content, show your support by subscribing to the free weekly newsletter, which includes the weekly articles as well as additional comments from me. There are great reasons to do so, and subscriptions give me motivation to continue writing these articles! Subscribe today!